Recap

Before we jump into file descriptors and mmap, here’s a quick recap from the previous post:

- Pages are fixed-size blocks of memory

- Page layouts are how data is kept inside those blocks

- Mint’s page layouts are just what Mint needs for its use cases

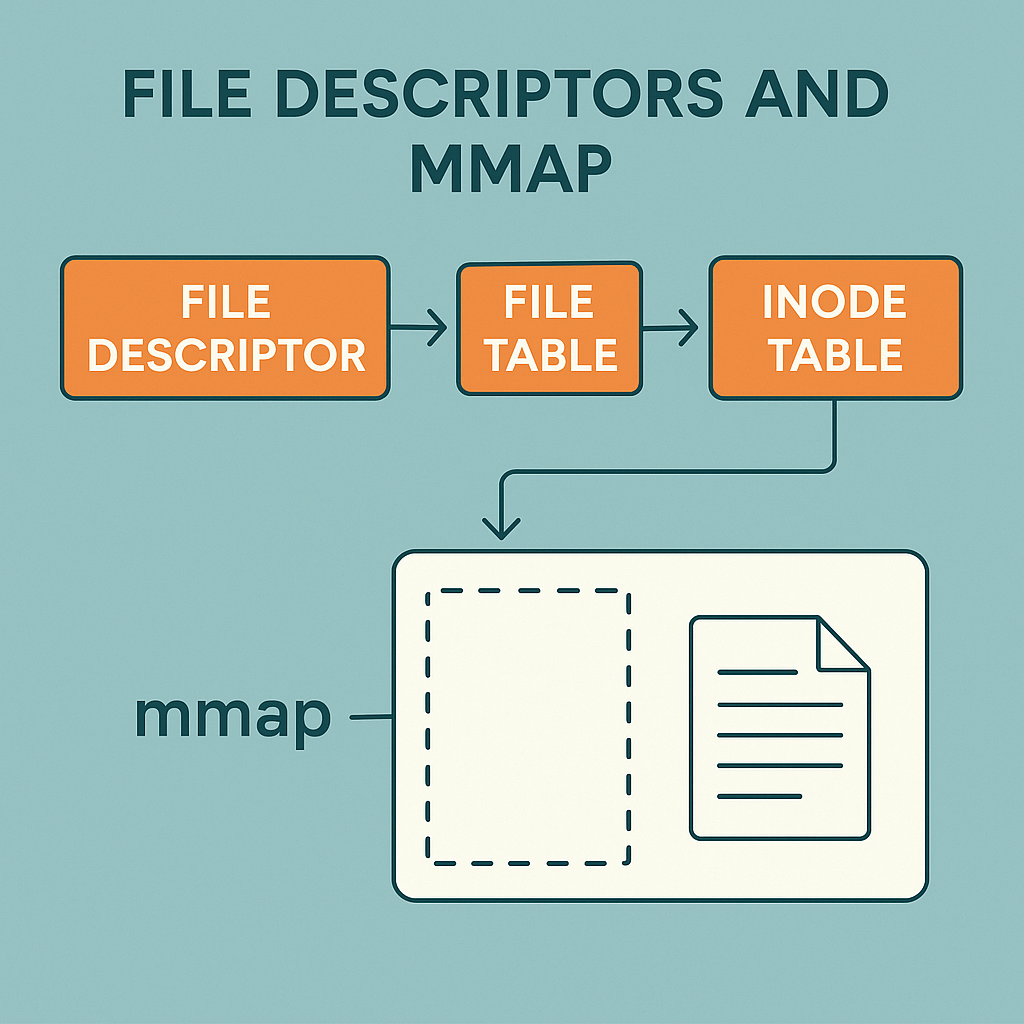

This is the base we’ll use to understand how files work in the OS. Mainly, we’ll talk about file descriptors and how mmap uses them.

File descriptors

Every time a process opens a file, the OS returns a number. That number is called a file descriptor, and the process uses it to talk to the file from that point on.

The first three are fixed and pretty standard:

0→ STDIN1→ STDOUT2→ STDERR

After that, it’s just the next available number — so if you open another file, you’ll probably get 3, then 4, and so on.

But here’s the thing: that number by itself doesn’t hold any file data. It’s more like a pointer into a bunch of tables that the OS maintains behind the scenes. These tables know all the details — which file, where the cursor is, what permissions we have, and so on.

You can think of it like this:

file descriptor → file table → system-wide open file table → inode table

Let’s break that down.

File descriptor

This is just the number the OS gives you when a file is opened. It lives inside the process. The number itself is nothing special. It just points to an entry in the process’s file table.

File table

Every process has its own file table. So Mint gets one, your terminal gets one, your browser has one too — all separate.

Each row in the table tells the OS:

- What file descriptor this is

- Where the current read/write pointer is

- What access mode we asked for (read, write, or both)

- And a pointer to something called the system-wide open file table

So when you run a read or write, this is where the OS looks first — “What file is this process talking about? What offset? What permissions?”

System-wide open file table

This is shared across all processes. It keeps track of every file that’s currently open in the system.

Each entry here says:

- “This is the actual file we’re dealing with”

- “Here’s a pointer to the inode”

- “These are the open modes (read/write)”

- “This is how many file descriptors are pointing here”

So if Mint and another process both open the same file, they’ll each have their own file descriptor and their own file table entry, but they’ll both point to the same row here.

This is how the OS allows file sharing safely.

Inode table (aka index table)

This is where the actual file metadata lives. It has details like:

- File size

- File permissions

- Created/modified timestamps

- And pointers to the actual data blocks on disk

When the OS reaches this point, it knows exactly where the file lives on disk and how to access it.

Even a simple read or write goes through this full chain. It feels a bit much for something that looks like just a file open — but the OS has to juggle a lot: multiple processes, multiple access modes, safe sharing, and tracking everything properly.

This entire setup also explains how mmap works. mmap needs the file to be open — so it relies on this exact system to connect your memory directly to parts of the file.

mmap

When we generally try to write to a file, we:

- Make a syscall to read the file.

- Copy the content to our program’s memory.

- Make changes.

- Make another syscall to write to the file.

This is an expensive process, as it has multiple syscalls and data copies. This works fine for small use cases but becomes inefficient for systems like databases. This is where mmap comes into the picture.

mmap provides a clean way to read and write data into a file, without copying.

I have used the word “copy” multiple times here, and it might make you wonder, “What the hell is getting copied?”. Let me explain.

When you do a read() operation on a file, the file is loaded into the kernel space (OS), and then the data is copied into the user space (our process). This is what I mean by copy. Consider a case where we want to access a large file. The copy from kernel space to the user space is resource-intensive.

mmap moves around this problem by directly mapping one page at a time into the user space. The key difference here is one page at a time. Even if the underlying file is large, we access only a specific part of the file at a time. The file is not completely read. This is helpful in areas where we need frequent reads and writes.

With respect to mmap’s relationship with file descriptor, mmap uses the file descriptor to fetch the page from an open file.

This covers the basics of file descriptors and mmap. Now, we can go ahead with the implementation of our pages.